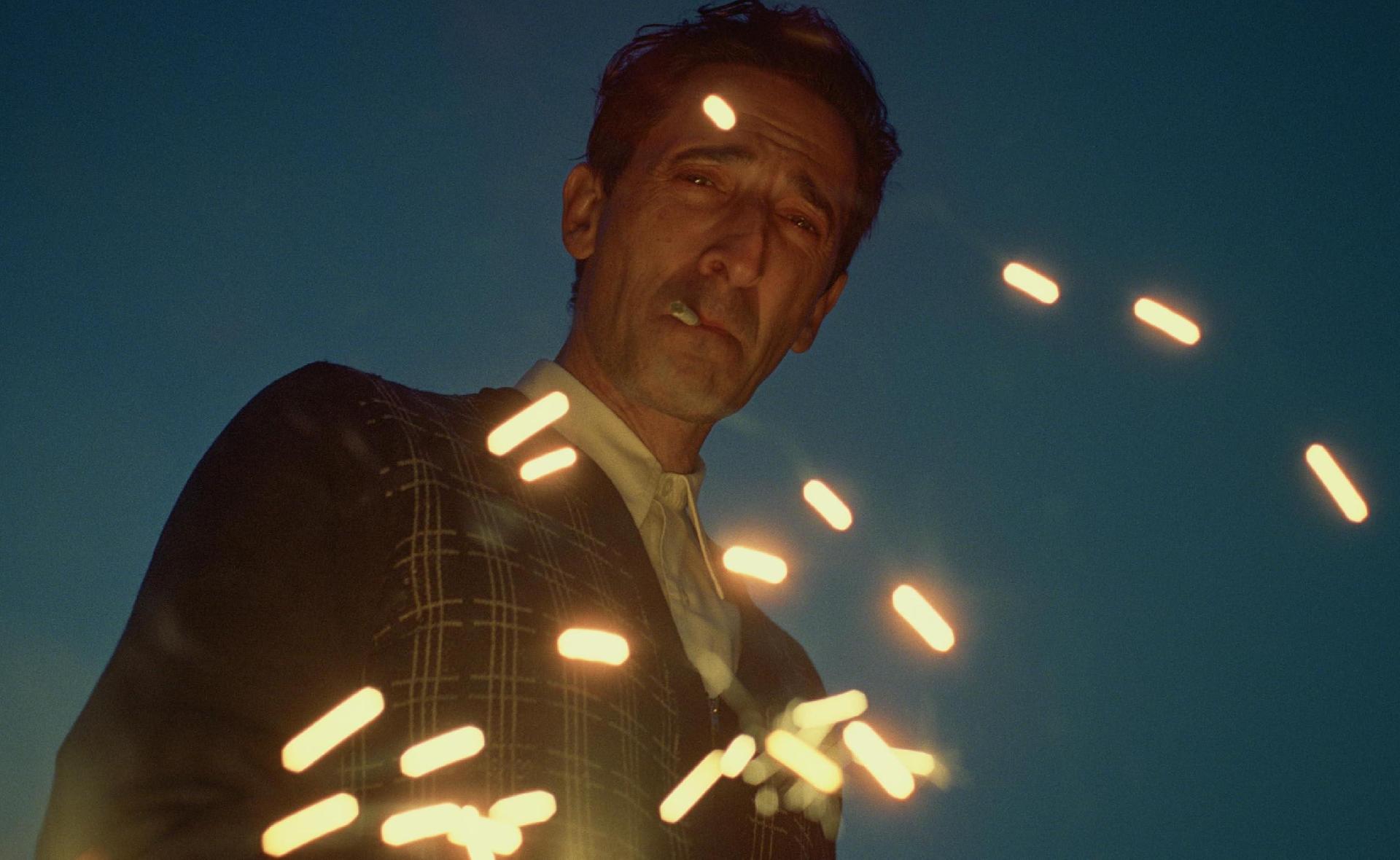

Brady Corbet’s cinematic tour-de-force The Brutalist sweeps numerous accolades in this year’s awards season. The harrowing epic follows the life of a Hungarian-born Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor, László Tóth (Adrien Brody). It is centred on the portrayal of an immigrant struggling to achieve the American Dream, who has his life turned around by a wealthy industrialist.

The film was almost entirely shot in Budapest, linking Adrien Brody closer to his character, through his Hungarian heritage. The actor said he was inspired by his family’s own immigration story, as his mother, photographer Sylvia Plachy, fled Hungary with her parents after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution.

Albeit the protagonist is a fictional character, the audience and professionals alike agree that the life and work of Hungarian architect Marcel Lajos Breuer was a strong inspiration for Tóth’s story - in the early 1950s, Breuer was commissioned to design a big brutalist church on a hill, just like Tóth – only it was in Minnesota, for Benedictine monks.

Modernist architect Marcel Lajos Breuer (1902-1981) became famous for his iconic tubular steel chairs, the Wassily and the Cesca, however, few people know the wide variety of brutalist buildings he designed worldwide.