Raekoja plats 2, 20307 Narva

In 2021, we celebrated the centenary of the establishment of Hungarian-Estonian diplomatic relations as Estonia’s de jure recognition by Hungary took place on 24th February 1921. On this occasion, the Institute and Embassy of Hungary prepared the bilingual roll-up exhibition "Small nations in the tide of history - One-hundred years of Hungarian-Estonian diplomatic relations", presenting the events leading to the establishment of diplomatic relations and its main events. From 8th April to 9th May 2022 the exhibition is shown in Narva College of University of Tartu.

Until the First World War, political relations between the two countries and nations were basically ad hoc, related to the prominent historical events of different eras and regions. In the 16th century, the Hungarian hussars of the Transylvanian prince and King of Poland, Stephen Báthory, also fought against the troops of the Russian tsar in southern Estonia. Although the prince himself never visited Estonia, he granted Valga city rights and in Tartu, established a Jesuit college and a training centre for interpreters. By the end of the 19th century, scientific and cultural relations had strengthened, based mainly on Finno-Ugric language kinship.

The two countries found themselves in radically different circumstances after the First World War. On one hand, separating from the Russian Empire, Estonia successfully fought a war of independence against the Soviet and Baltic German armies between 1918 and 1920. Hungary, on the other, lost about two-thirds of its territory and one-third of its population as a result of the Treaty of Trianon in 1920, and found itself in the hostile ring of neighbouring countries. The primary goal for both of them was to establish friendly relations with all the countries that were open-minded and in which they had a greater chance of awakening goodwill towards themselves.

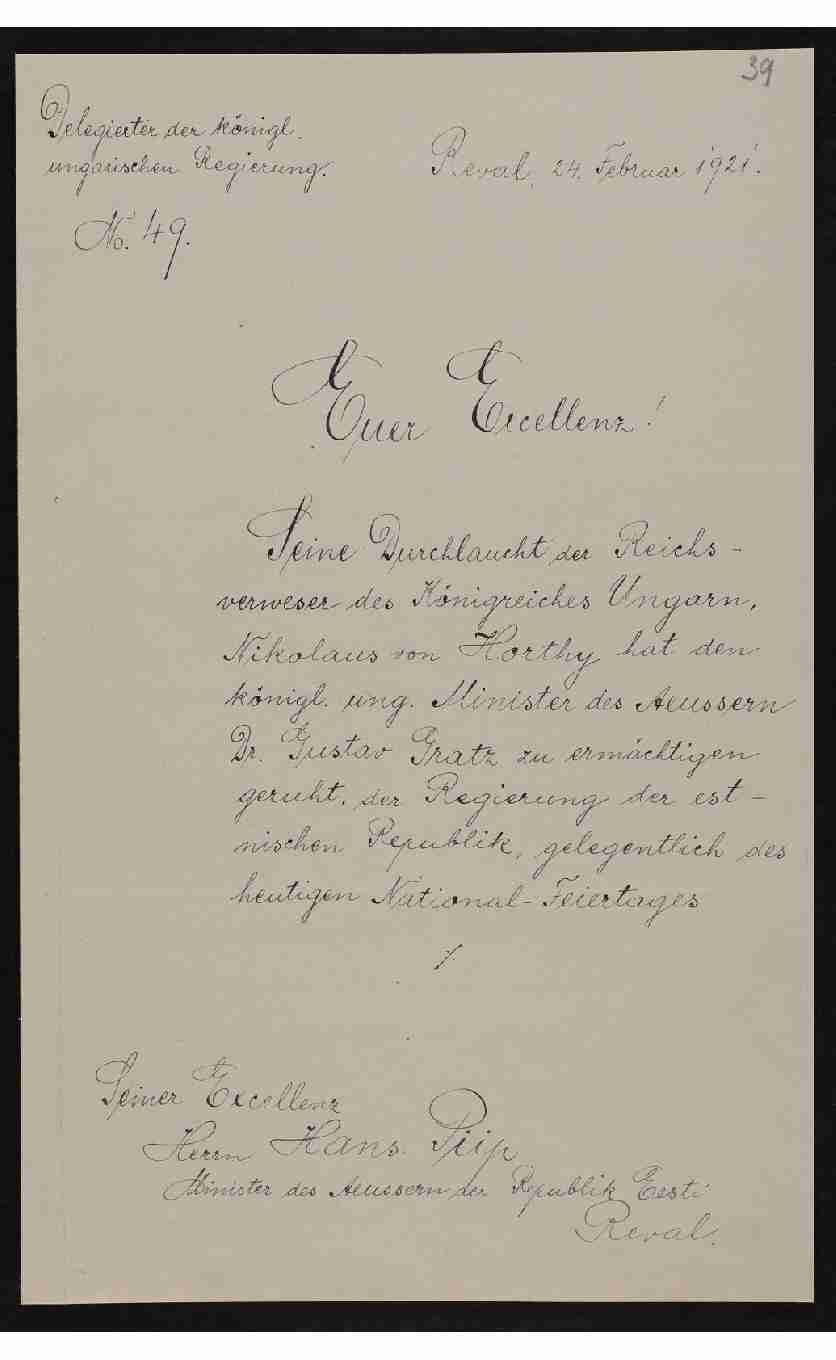

The reason for official contact was to repatriate Hungarian soldiers captured during the war, from 1920. Although Hungary and Soviet-Russia were not formally in contact, they agreed to a prisoner exchange, and on the suggestion of Moscow, they chose Estonia as the venue for these negotiations. The Hungarian delegation—headed by Mihály Jungerth, a diplomat dealing with prisoners of war in the Hungarian Royal Ministry of Foreign Affairs—arrived in Reval (Tallinn) on January 1st, 1921, and its operation had characteristics of a diplomatic representation from the very beginning.

Hungarian diplomat Mihály Jungerth, later the first envoy to Estonia. Source: National Archives of Estonia (EAA.1770.1.138.31)

After Estonia was recognised on January 26th, 1921 by the five great powers leading the Paris peace talks (the United States, France, Japan, Great Britain and Italy), and then by the Scandinavian states and Germany, Hungarian recognition also became timely. However, Foreign Minister Gusztáv Gratz cautiously asked for confirmation of the news, and for the names of the Estonian Head of State, Prime Minister and Foreign Minister to be disclosed. On 28th January, Estonia was only de facto recognised by Hungary through its embassy in Berlin. Following official diplomatic confirmations, Jungerth soon suggested to Gratz that Hungary recognise Estonia de jure on February 24th, 1921, the third anniversary of Estonian independence. Jungerth received the official telegram of recognition on February 23rd, which he handed over to Foreign Minister Ants Piip at 2 pm. The content of the telegram was widely known in the city already that afternoon. In his reply, the Minister asked to convey the kindred gratitude of the Estonian Head of State, the Estonian Government and the Estonian people and expressed his belief that with the recognition, Hungary delivered the most beautiful present for their national celebrations.

In the following years, Hungary decided to open an embassy in Tallinn. As a result, the Hungarian and Finnish embassies were housed together in a building owned by President Konstantin Päts between 1924 and 1928, thus strengthening the consciousness of Finno-Ugric kinship. At the same time, Jungerth handed over his credentials and represented Hungary in the three Baltic States and Finland first as chargé d’affaires, and from 1924, as an envoy. At the same time he was tasked to observe the Soviet Union and in spite of the lack of diplomatic relations, requested to have regular contact with Soviet embassies and diplomats. The new embassy began the selection of honorary consuls, whose activities also sought to further strengthen the favourable image of Hungary in Estonia, despite personnel changes.

Jungerth did much to promote scientific relationships as well. As early as 1921, he visited the University of Tartu and proposed the exchange of lecturers and students, and started the establishment of a Hungarian Institute within the university. Considering the realities, the Hungarian lector Elemér Virányi finally started his activity at the university in 1922. Law professor István Csekey joined him in 1923, who began teaching administrative law, and that same year organised the Hungarian Scientific Institute in Tartu, becoming its first director until 1931. Besides them, several other Hungarian lectors and professors were active in Estonia, contributing to the development of Estonian-Hungarian relations, spreading knowledge about Hungary, and contributing to the foundations of Estonian science. Increasingly close ties also extended to the fields of culture and sports. The movement of the Hungarian embassy to Helsinki for economic reasons caused a slight break in official relations in 1928. From Helsinki, Hungary secured diplomatic representation to the Baltic countries, but the reception of Hungarians in Estonia was nevertheless outstanding.

With the Soviet occupation of Estonia in 1940, official interstate relations were suspended but not completely abolished, and co-operation in culture took over. After the war ended, it was possible relatively quickly to learn Hungarian again in Tartu, and despite of the difficulties, many prominent Hungarian-speaking linguists graduated during the 1950s and onwards. From the sixties, several Hungarians from Transcarpathia arrived in Estonia, on one hand taking part in language teaching and on the other becoming crucial in organising the Hungarian diaspora in Estonia and promoting bilateral relations. It was also possible to foster cooperation through the Hungarian-Soviet Friendship Society, and taking advantage of it, they established the first twinning relations, continuing to this day.

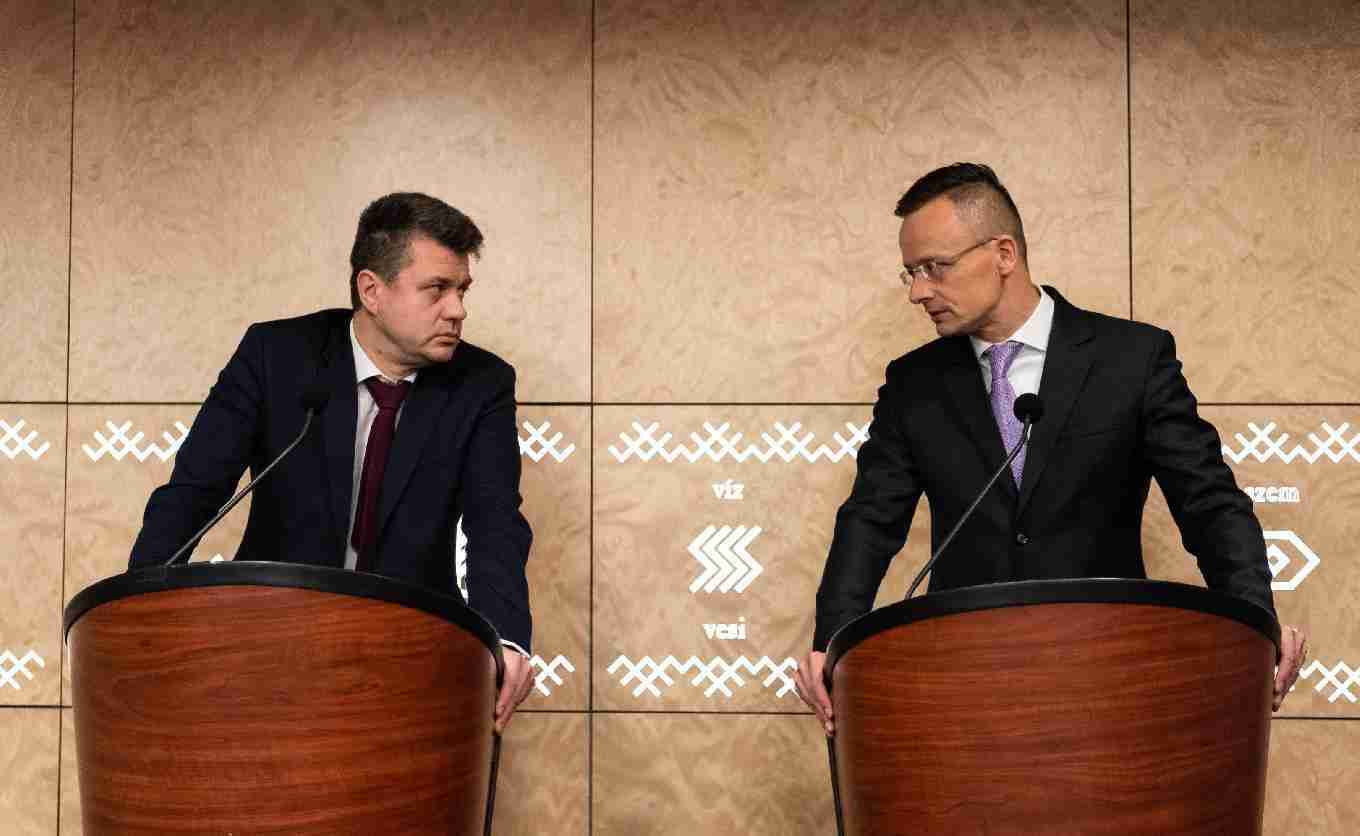

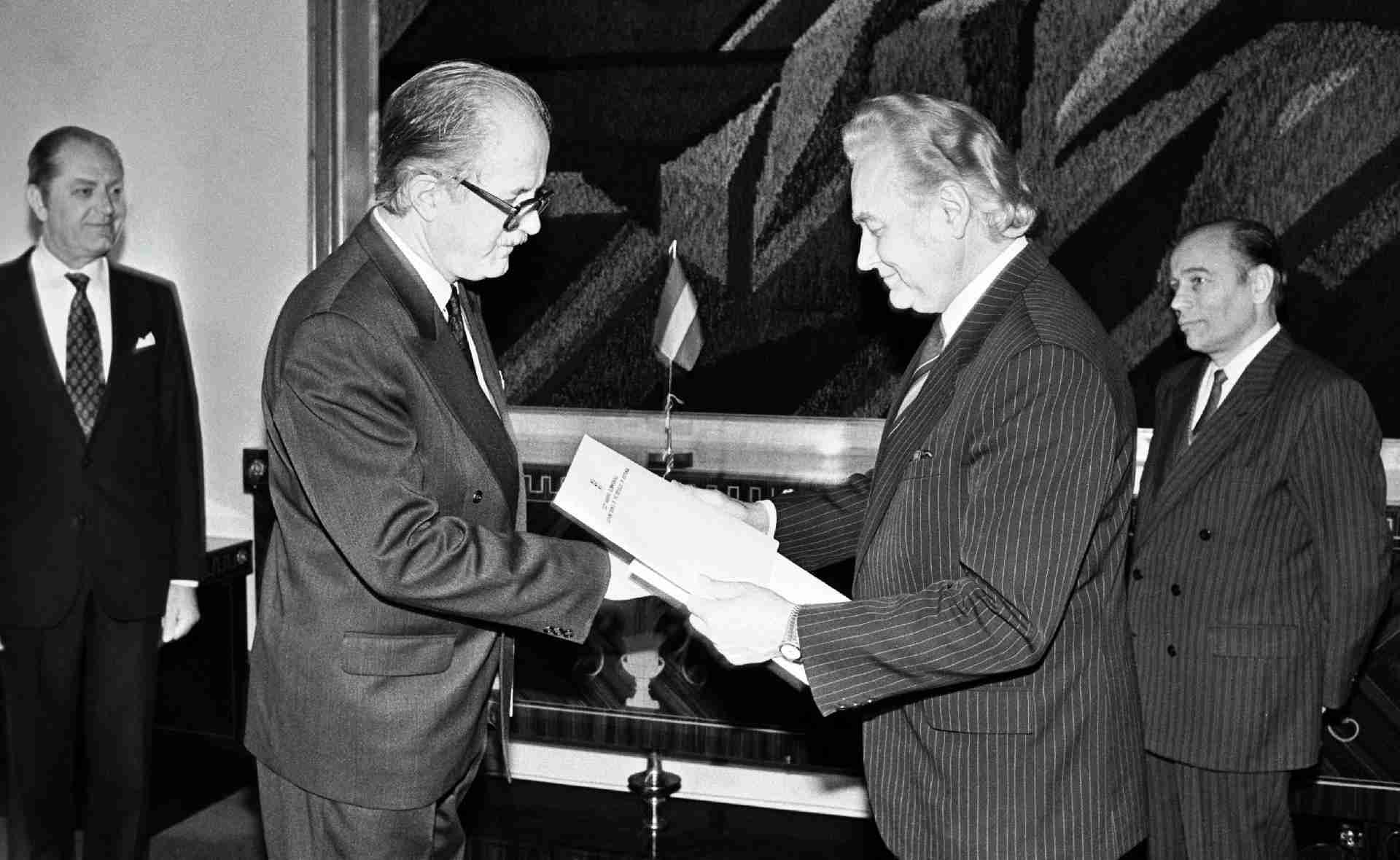

Events leading towards the re-establishment of diplomatic relations accelerated in the wake of the Moscow coup in August 1991. Estonia announced the restoration of its independence and initiated its recognition again, while proposing the establishment of cultural offices in both Budapest and Tallinn. Hungary reacted quickly: it recognised Estonia’s independence on 24th August and then re-established its diplomatic relations with Estonia on 2nd September. Ambassador Béla Jávorszky from Helsinki presented his credentials to Arnold Rüütel, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Estonia, on December 10th, 1991, thus restoring diplomatic relations between the two countries after a 51-year hiatus.

Hungarian Ambassador Béla Jávorszky (left) presents credentials to Arnold Rüütel, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Estonia (1991). Source: National Archives of Estonia EFA.204.0.171640)

In the following decades, bilateral relations have gradually continued to strengthen. In 1992, a cultural institute was opened in Tallinn, then again in Budapest in 1998, while the embassies both reopened in 1999. From 1993, a lector sent from Hungary strengthened Hungarian language teaching at the University of Tartu. As the fruit of his and his successors’ work, a new generation of translators dedicated to the Hungarian language and culture grew up. The two countries became members of NATO and the European Union by the beginning of the 21st century, following the other’s experiences closely and in consultation with each other. Several bilateral treaties and agreements and high-level visits underscored the strengthening relations. A further good practical example is the Gripen fighter jets of the Hungarian Air Force participating in the protection of the airspace of Baltic States – including Estonia – in 2015 and 2019, in the framework of NATO’s Baltic air-policing mission. In 2022, the Hungarian jets will once again arrive in the Baltics, strengthening the defence policy cooperation of the three Baltic States and Hungary.

There is a common understanding regarding the goals: getting to know each other better, strengthening political, economic and cultural ties, engaging the younger generations and rousing sympathy for each other’s culture. The centenary year is an excellent opportunity to present the unique history of relations between the two kindred people via the development of diplomatic relations and to further strengthen them through various cultural programs.